Your cart is currently empty!

From the biggest Elephant

to the littlest Fly

From every fish in the sea

to the birds in the sky

Animals are all around us

Dolphins are animals

That’s plain to see

Just like Owls

and Salamanders

and the Anoles in the trees

No matter how different they appear, All of these are pretty easy to recognize as animals.

Maybe the first you think of are the “fluffies”, or mammals

like dogs and cats, cheetahs and rats!

That’s okay, too! You’d still be right and definitely not alone.

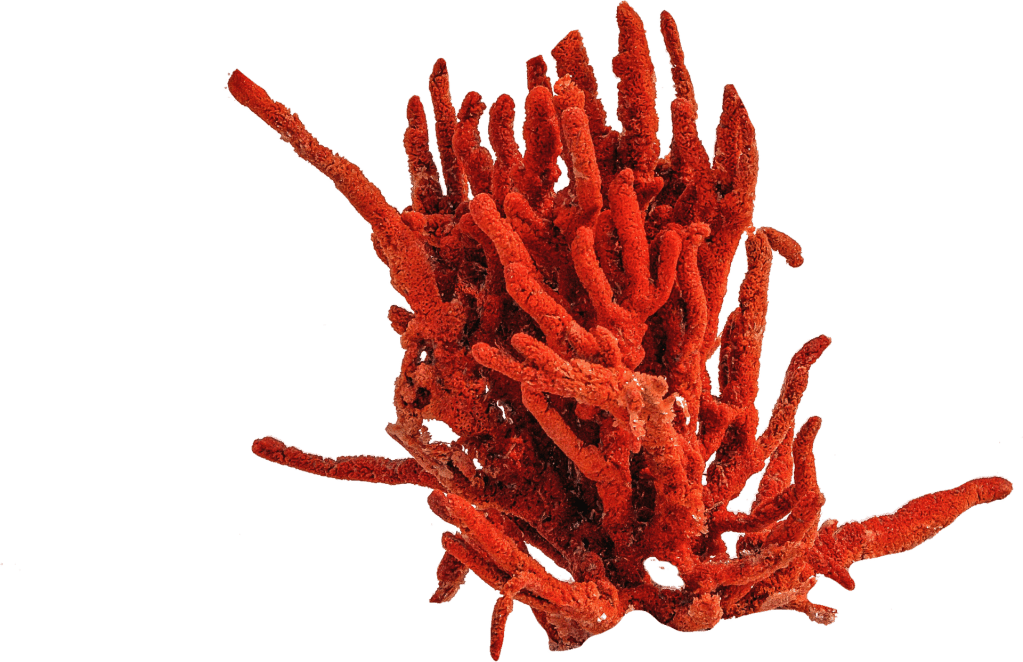

But what about coral?

or jellies?

Or sea sponges?

Or these things?!?!?!

(bryozoans)

They are animals too!

To get super sciencey for a moment, animals as a group are multicellular (many-celled), eukaryotic organisms belonging to the kingdom Animalia.

(Point of clarification: Kingdom Animalia is not a place. It’s a category of life, like, I don’t know, a genre of movie?)

Something like 1.5 million species of animal have been formally described, or identified, by science. Of those, about 1 million are insects!

Yet it’s estimated that in reality there are nearly 7 million animal species on this planet, right now. And it’s more than possible that insects and other invertebrates make up 99% of all animal species!

Animals range in size from 0.00033 inches to 110 feet and virtually every shape and pattern imaginable.

Yet despite their incredible diversity, there are some key traits that they all share.

Sure, many animals have eyes

But not all do!

When we say shared traits, we mean something a little more basic.

Feeding and Digestion

Like all life, animals need energy to survive.

But unlike other living things (plants, some bacteria, etc), animals can’t just make themselves food

Animals need to eat, so we call them heterotrophs (hetero- meaning other + trophos meaning feeder)

After obtaining food, animals have to digest it in some way. In some animals, like sponges, this happens in specific cells. In others, like us, it happens within our organs.

Support

95-99% of all animals are invertebrates

- Animals without backbones

Their bodies are covered with exoskeletons, a hard or tough outer covering that provides support

These outer skeletons perform several key functions

- Protect soft body tissues

- Prevent water loss

- Protect against predators

As the organism grows, it has to shed, or molt, its exoskeleton and replace it. Of course, some animals have internal skeletons or endoskeletons

These are internal structures that provide support, like our skeletons!

Some invertebrates, like sea urchins, have both exo- and endoskeletons

If an animal has an endoskeleton + a backbone, it’s called a vertebrate

What makes up an endoskeleton varies. Animals like urchins and sea stars have skeletons made up of calcium carbonate. Sharks and rays have skeletal systems made up of cartilage. Of course, fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals have bone.

Cell Structure

No matter its adaptations or habitat, animal cells DO NOT have cell walls like plants

In all animals, except sponges, cells are organized into specific types of tissue with specific jobs

- Example: muscle tissue, brain tissue, etc

Movement

Having cells organized into tissues, like muscle and nerve tissue, has allowed animals to become the envy of Life Track & Field day. Animals can move, and fast!

Okay, not all animals are fast, but all animals are at least motile for a part of their lives. Some simpler life, like sponges, start out motile and later become sessile, which basically means unmoving.

Reproduction

Ah, the “birds and the bees” talk…

Most animals reproduce sexually, but (and here’s the shocker) not all! Some are able to reproduce asexually, which is pretty neat.

In terms of the sexual type, it typically goes like this: males produce a special type of cell with half the amount of genetic information as a normal cell called sperm. Females do the same, but we call their special cells eggs.

Yet, even still, some animals (take earthworms for example), are what we call hermaphrodites. These animals produce eggs and sperm at different times. They still need another member of the species to reproduce, but the role they play, or what they provide, can change.

After a sperm penetrates an egg and the good ole swapping and merging of genetic info begins, we say the egg has been fertilized. Now we get to call that fertilized egg by a new name—Paul.

Just kidding, it’s a zygote.

The thing about fertilization is it can take place in the body or outside the body. Different animals have different strategies that work best for them and their environment.

Then there’s that nifty trick called asexual reproduction. This can occur in a variety of ways:

- Budding- offspring basically growing, or budding, off of the parent

- Parthenogenesis- when females of a species are able to produce eggs and eventual offspring, no fertilization required

- Fragmentation- where the broken pieces of a parent can themselves grow into an adult animal

- and a couple others.

Bottom line is this: animals, while tricky, are possible to define. In the coming weeks, I’ll be developing a series around animal basics as a lead up to our new podcast series, Class, where we explore all of animal life one class at a time. Each season, a new class. Each episode, a new phylum.

Next time, I’ll be exploring animal development, body plans, and more fun anatomy stuff from across the animal kingdom. Stay tuned!

Support The Wild Life for as little as $1 per month

The Wild Life was created in January of 2017 by, me, Devon Bowker (He/They) after finishing my degree in wildlife biology. It’s been amazing to see how things have changed over the past 5 years, both personally and here. I have tons of ideas and projects in the works and cannot wait to share them with you. Whether you’re a long-time follower or new to The Wild Life, thank you for being here.

Leave a Reply