Your cart is currently empty!

This Ghostly, Parasitic Plant Survives by Hacking the Wood Wide Web

Published by

on

This Labor Day weekend, my wife and I (with our son on my back) hiked 15 miles across several of the Minnesota North Shore’s state parks. It was midway through our hike at Cascade River, just south of Grand Marais, where I spotted something in my periphery that I had never seen before. Now, I have to admit, I had no idea what I was looking at. The identity and nature of this seussian xenomorph completely alluded me. At first glance I concluded that it had to be a mushroom or fungi of some kind. Yet after leaning in for a closer look I discovered leaves and what appeared to be a flowering structure–traits which a fungi would not have. So, I did what any good millennial or naturalist would do and snapped a photo. Fortunate enough, we happened to be in the one spot of the park that seemed to have cell service—at least enough to do some quick searches. Yes, I could have waited until later, but my sense of curiosity and need to know insisted otherwise. After roughly 30 seconds, I’d found its name, Monotropa uniflora, and a life history story that was unexpectedly fascinating.

As I said before, I hadn’t been sure on the planty-fungi nature of my find, and I was certain others would have the same dilemma. So I turned to Instagram to test my hypothesis. 70% of respondents sided on fungi, while 30% (including my wife who doesn’t really count since she had already known at this point) sided with plant. The minority were right.

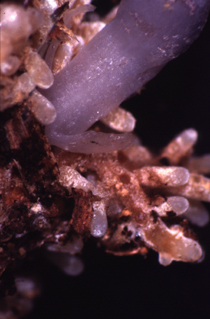

This ghostly plant goes by several common names—ghost plant being one of them. Others include ghost pipe, corpse plant, or as it is referred to locally, Indian Pipe.

The first thing you may notice about this plant is that it is a pinkish white with flecks of black—certainly not colors often associated with a plants leaves and stems. See, as you may already know, the green pigment commonly associated with most plants comes from their chlorophyll. These chlorophyll perform several functions, all vital to photosynthesis, with the main one being the absorption and transfer of light energy. The Indian Pipe, as you may have gathered by this point, lacks those vital ingredients for photosynthesis.

So how does it get its energy? How does it make food to survive? Well, it doesn’t.

The Indian Pipe is categorized as a myco-heterotroph. This means that they get their energy through a symbiotic relationship with a certain host—fungi!

They tend to make their home, er, host of fungi in the family Russulaceae which produce over 1,900 species of gilled mushroom. Remember, mushrooms are but the reproductive organs of fungi, whose bodies exist beneath the soil in a vast network of fine white filamentous tubes called hyphae, which grouped together in dense strands are referred to as mycelium. This will become relevant in a second.

You see, fungi being fungi and not plants also lack chlorophyll, meaning, fungi aren’t capable of making their own sugar. Those long, incredibly thin hyphae tubes work be creeping their way through the soil, into and between rocks, or a dead bird, or pocket of minerals, and once there, they secrete a dissolving acid which allows them to slurp of a nice healthy broth of nutrients.

Now, admittedly, this is a bit of a major oversimplification of the process, as will be the rest of this brief explanation, but that’s intentional. Season 2 Episode 7 of The Wild Life will go into this entire process and other fascinating facts about the fungus among-us, and, of course, we want you to come back to listen, right?

So, fungi are actively assisting in the decomposition of dead stuff and mining for rocky stuff, which means they are truly great at gathering minerals, but not so much when it comes to sugar, no. Which is why fungi often must turn to their much larger, friendly neighbor to borrow a cup of sugar. In exchange, they’ll lend some minerals…and phosphorus, nitrogen, other micronutrients, and even a surprisingly large amount of water!

I’m referring to trees, of course, or rather their roots. That family of fungi I mentioned earlier? Well, they are what you would call mycorrhizal, meaning they colonize plant roots to form an intricate symbiotic exchange system connecting plant and trees to other plants and trees in a massive underground nutrient exchange and savings vault system called the Wood Wide Web.

This means that the Indian Pipe, non-photosynthetic, parasitic plant we began this post about is essentially inserting itself into this system like old-west train robbers or an Oceans heist to steal the hard earned sugar from the fungi which was originally made by another photosynthetic plant from the fungi! If that isn’t excitingly mind boggling and fascinating to you then we can’t be friends.

And to make matters more interesting, the lives of the Indian Pipe are incredibly fleeting and difficult to predict, living what is referred to as an ephemeral existence. They require very specific conditions, the right amount of moisture after a period of dryness, in order to grow. Once they begin, they are typically full grown within just a few days. However, not needing light for photosynthesis means they can grow in a wide range of light conditions, including the very dark. They first pop up in early summer and will continue this cycle of a parasitic existence until early fall, their waxy white bodies standing up to a foot off of the forest floor before withering to brown and black as their seeds mature and fall to the ground to begin again.

3 responses to “This Ghostly, Parasitic Plant Survives by Hacking the Wood Wide Web”

-

I spotted some Indian pipes at Quarry Park about a month ago and took some photos! Love those plants! Thanks for your cactus walk this evening at Quarry Park. So informative!

-

[…] Read the blog this is based on and see more images of the find here […]

-

Found these up elk creek outside of shady cove near lost creek lake. Grew next to filberts at about 3500 feet elevation

Leave a Reply